You can’t look at the news lately without hearing the word “tariff.” There’s also been a lot of discussion about whether they are good or bad. Historically speaking, tariffs have been used for a variety of purposes, but ultimately, they will always raise the price of imported goods, which increases the cost of manufacturing inputs and retail inventory.

As a quick refresher on your Econ 101 class, tariffs are used:

- As leverage for negotiating trade deals or retaliating against countries that tariff U.S. goods.

- As a means to grow U.S. federal revenue.

- To encourage U.S. firms to reshore their operations, invest in domestic production, and diversify the U.S. manufacturing sector.

- To spur U.S. companies to buy domestically produced goods or find other foreign sources not under tariffs.

Last year, President Trump campaigned on using tariffs for all these purposes. In negotiating trade deals, tariffs can be short- or long-term, but their use in building federal revenue and encouraging reshoring would suggest longer-term tariffs — potentially for the length of the current presidency.

How long Trump’s tariffs are sustained or how substantial they will be remains unclear. But, let’s take a closer look at how the imposition of tariffs might impact certain U.S. industries — some for better, some for worse — and also the hit consumers might feel to their wallets.

Tariffs affect industries and consumers alike

Tariffs have a disproportionate impact on industries with some suffering and others benefiting. Ultimately, end users of goods and services typically pay more or may forego discretionary purchases.

Industries that buy imported goods under tariff must deal with the higher costs, which can negatively impact profit margins. Companies typically attempt to pass the added costs to customers in the form of higher product prices or service fees to preserve the business’s profit margins. However, the market will only bear so much price increase before consumers and businesses pull back on purchases or seek lower-cost alternatives.

Aside from the percentage markup of the tariff, the type of product being imported is a factor too. For instance, a 20-25% markup on the cost of commodity items, like screws or rubber bands, is much easier to pass on to consumers than a 20-25% markup on high-priced items like automobiles or industrial machinery.

To avoid higher costs related to tariffs, U.S. firms may opt to source goods from domestic suppliers or foreign suppliers that are not tariffed. While U.S.-sourced goods may not offer significant cost-savings, they may provide other benefits, such as higher quality, faster access, or customization.

But in cases where alternative sources of goods are limited or don’t exist, firms may be forced to pay the higher price or modify their production or product line to do without the imported item or use a substitute item in production.

This often requires substantial upfront investment, costly changes in production processes, and added sourcing costs. Firms may therefore postpone such moves until more certainty develops around the duration of the tariffs, what goods are impacted, and the size of the tariffs.

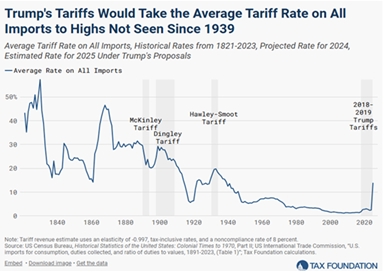

Average tariff rate on all imports:

- Smoot-Hawley 1930: 20%

- Trump 2018-2019: 3%

- Trump January 2025: 14%

Foreign countries may hit back

And don’t forget that it’s a two-way street: U.S. tariffs on imports can result in retaliatory tariffs from other countries. Tariffs on U.S. goods sold in other countries can reduce demand for U.S. exports, particularly for high-priced goods, highly specialized goods, or crops that can’t easily be replicated or grown in the importing country or sourced from another country.

The cost-benefit of producing abroad can be negated by high tariffs when the firm’s goods are imported back into the U.S. To avoid tariffs on their goods, some U.S. firms have begun the process of reshoring part or all of their foreign operations.

Indeed, when coupled with potential industrial incentives from the federal government to reshore, more domestic firms are weighing the costs and benefits of bringing production back to the U.S. However, reshoring often comes with big challenges. Setting up a manufacturing plant and ramping up production requires significant investment in time, infrastructure, labor, and materials.

Real-world examples of tariffs’ impact

Here are examples of how tariffs are impacting industries and their responses:

Automobile dealerships

Auto industry leaders are increasingly sounding the alarm on the Trump administration’s threats to tariff automobiles. With prices of new cars already up significantly to an average of $50,000, the effect of tariffs could add an average of $9,000 per vehicle to the cost, according to an Anderson Economic Group analysis of inventory and where vehicles are assembled and built.

Auto manufacturers like Ford and Stellantis are halting production on certain models, and a protracted trade dispute could eventually result in layoffs across the industry. In addition, if the tariffs apply only to Mexico and Canada, carmakers from Japan, South Korea, and Germany stand to flood the U.S. market.

Medical device manufacturers

About 75% of medical devices marketed in the U.S. are manufactured outside of the country, including 13.6% of them in China, according to data and analytic company GlobalData’s medsource database. Tariffs could drive up costs, temporarily stifle innovation, and force firms to rethink supply chain strategies to protect their bottom lines.

The American Hospital Association thus has requested an exemption from tariffs on medical devices and pharmaceuticals made in the three countries targeted by the Trump administration’s planned 25% tariff.

Semiconductor manufacturers

Competition for domestic producers of some types of semiconductors could increase as a result of the proposed new tariffs. Major semiconductor manufacturer TSMC said in early March that it will invest “at least” $100 billion in chip manufacturing plants in the U.S. over the next four years as part of an effort to expand the company’s network of semiconductor factories.

The U.S. government considers TSMC’s heavy Taiwanese presence a strategic risk because of growing threats from the mainland Chinese government, according to TechCrunch. If TSMC begins producing its semiconductor chips in the U.S., domestic producers of a wide range of products that use semiconductors may benefit from cost-savings, proximity to a major supplier, and reduced supply chain risk.

Industrial machinery distributors

Protectionist tariffs under the second Trump administration would encourage some businesses to onshore their supply chains, reducing risks from overseas sourcing and creating opportunities for U.S. distributors to replace overseas suppliers, says BlackBean Marketing. Indeed, reshoring and the resultant investment in industrial machinery infrastructure is expected to accelerate over the next 3-5 years as more businesses return to U.S. production.

Grain and oilseed milling

President Trump’s trade policy could present an opportunity to oilseed millers as import tariffs on vegetable oils spur the U.S. crush industry to build new plants and expand capacity, AgWeek reports. Plans for domestic expansion have previously been hindered because the U.S. market has been awash in cheaper global supplies of feedstocks from China, Brazil, and Canada.

As U.S. imports of vegetable oils decline, domestic producers will see increased demand and purchase more corn, soybeans, and other oilseeds from U.S. farmers, who could see their export markets dry up if foreign nations, notably China, retaliate with tariffs of their own.